From Compassion in Her Youth To Courage Amid Her Own Pain

Remembering Sarah Hyde

By Patricia Sullivan

The Washington Post, Sunday April 1, 2007

As an artist, a teacher and an entrepreneur, Sarah Hyde had a certain something that made people take notice.

“People could get very quickly and easily swooped up in her energy, infected by her enthusiasm,” said her husband, Jack Kline.

“You would certainly know she was intelligent, she was lively, she was interested in life. You might not know she was an artist or a teacher,” said her collaborator and neighbor, Dianne Hunt.

“She was great,” said Carlisle Walters, a friend since 1971. She had a wonderful sense of humor, not in the sense of telling jokes, but being able to laugh at life’s ironies. She had a great laugh, too.”

The 59-year-old woman of many interests died of complications from a brain tumor March 8 at her hoe in Takoma Park. She had fought cancer, and the effect of the treatment, since 1999.

“She just dealt with it,” said Kline, a social worker. “It was unbelievable just how much aplomb, focus and courage she brought to it…and she never lost a certain dogged stamina to always try to do what was right.”

From her childhood on Watertown, NY, she struck others as a compassionate person, watching out for other children on the block and suffering at the death of her eldest brother when she was 13. She became fluent in American Sign Language and after college and graduate school worked as a teacher of hearing-impaired children with multiple disabilities. She also wrote and published a curriculum for those students and consulted across the country on its use.

She was so skilled that she was offered and administrative position at Gallaudet University, the nation’s premier college for the deaf and hearing-impaired. That was a turning point; she and Walters discussed it for hours until Hyde decided to throw herself into her original love of art, despite concern for her finances.

Hyde hung out at the Joy of Motion Dance Center near Dupont Circle, drawing female dancers in all manner of poses. She found two who became her regular models for dramatic portraits. Some of her art shows were juried by Alice Neel, a grand dame of portraiture.

“Sarah could capture the mysterious in women, she could capture the trauma of womanhood and she could capture the joy,” her husband said.

Hyde was commissioned to draw dancers at the Washington Ballet. In 1983, Hunt, who is a choreographer, approached her about an idea for a dance and visual art performance.

“Looking back, I think frankly that Sarah’s paintings were a higher level of artistry than mine at that point,” Hunt said. Over the next 18 months, they created “Life Drawing,” in which black-leotard-clad dancers, their hair spray-painted blue, performed around and with six larger-than-life paintings of dancers. The painting, which moved on wheels, fit together like a child’s puzzle. On the opposite side was an abstract color-field painting, and glowing red stripes marked the edges.

“For me as a choreographer, it was the most complete collaboration I ever had,” Hunt said. The piece was performed at least three times in 1985 at local venues.

But that was not all Hyde was working on. In addition to her master’s degree in education, she received a master’s certificate in sculpture and paining from the New York Academy of Art and a doctorate in fine arts from New York University in 1994, after six years of work.

Though raised as a Presbyterian, she began studying Hindu and Buddhist traditions in the 1960s and 1970s and considered joining an ashram led by Swami Muktananda. She retreated from that religious tradition in the 1980s but incorporated her knowledge into her doctoral thesis.

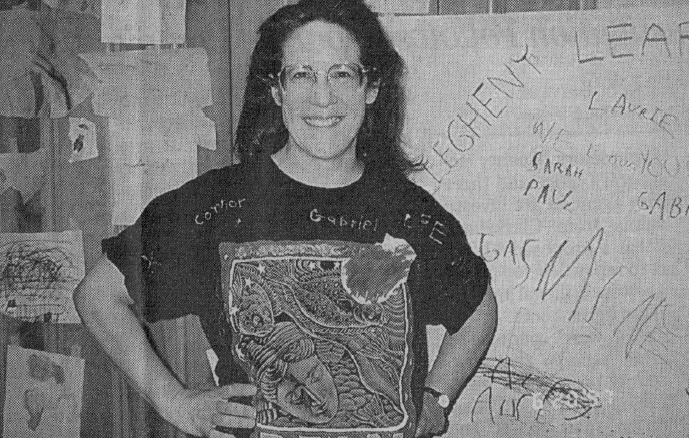

She taught at the Corcoran School of Art during the 1990s and started a preschool, the Allegheny Learning Center, in her home so she could be with her newborn daughter, Sophia. The teachers were fellow artists, and a waiting list quickly formed for potential students.

“She was doing a million things,” Kline said. “She did not want to get a video of her daughter’s first steps or a tape recording of her daughter’s first words.”

When cancer struck in 1999, the indomitable artist forged ahead for a year. But then she became disabled from radiation treatments and wasn’t unable to drive or paint or teach.

It was a struggle for her to find words and communicate what she wanted to communicate. She dealt with it with such dignity and humor and moved forward as best she could with her life,” Hunt said. “No self-pity. She certainly experienced frustration and expressed it at times. But all our neighborhood was amazed at her fortitude and good cheer. “