Paean To A Preschool

Remembering Sarah Hyde

by Sue Katz Miller

Voice, May 2007

Ten years ago, I was living in Brazil with my three-year old daughter and newborn son. My husband allowed as how it was my turn to choose where in the world, we would go to live next. So I sent an email to Marika Partridge in Takoma Park saying, “We’re coming. Find the girls a nursery school!” The girls, my Aimee and her Sally, were born we declared them best friends for life, whether they liked it or not. Marika emailed me back right away: “we will put the girls at Sarah Hyde’s.”

Officially, “Sarah Hyde’s” was called the Allegheny Learning Center, but we always just called is Sarah Hyde’s, which tells you something about the essential role of Sarah in this story. When Sarah Hyde died this spring after her long struggle with a brain tumor, every parent who was lucky enough to have stumbled on her basement preschool stopped to remember and appreciate the magical safe harbor she created for children on Allegheny Avenue. My Aimee is now a teenager, but Sarah Hyde’s was a primary catalyst in her evolving self-image as an artist and poet. And for me, Sarah Hyde provided gentle and necessary encouragement in that long and terrifying process: letting go of your child.

You would think that a three-year-old would be too young to go through culture shock. You would be wrong. When we arrived in Takoma Park, Aimee was disoriented and grief-stricken. She stood on the sidewalk in front of our new house screaming, “I hate this house! It smells like throw-up!” She mourned for the sounds of Portuguese, for her Brazilian nanny, for fresh passion fruit juice, for daily trips to the beach. When I said we were moving “home” to Takoma Park, I forgot that she had not lived in the United States since she was an infant, and that this was not (yet) her home.

On thing she did not miss was her Brazilian nursery school. Choosing a preschool is always a process fraught with parental anxiety. In part because of the limited choices in our very por city, I had unwittingly placed Aimee in a traumatically bad school. Each child was allowed to play with one toy each day, but only if they were good. There was no art on the walls. Need I say more?

So we arrived at Sarah Hyde’s pink bungalow with trepidation. And at first, I admit I was puzzled by Marika’s choice. In Sarah’s walk-out basement, kids were romping on some seriously grungy caved in couches, strewn with toys. The school space opened out into a small backyard filled with standard backyard swings. This was it? But Marika was insistent and utterly confident. “They didn’t care about the mess,” she recalls now. “It wasn’t meant to be neat and organized. It was meant to be kid-friendly, and tactile, and dreams-come-true. The kids could jump on the furniture, roll around.”

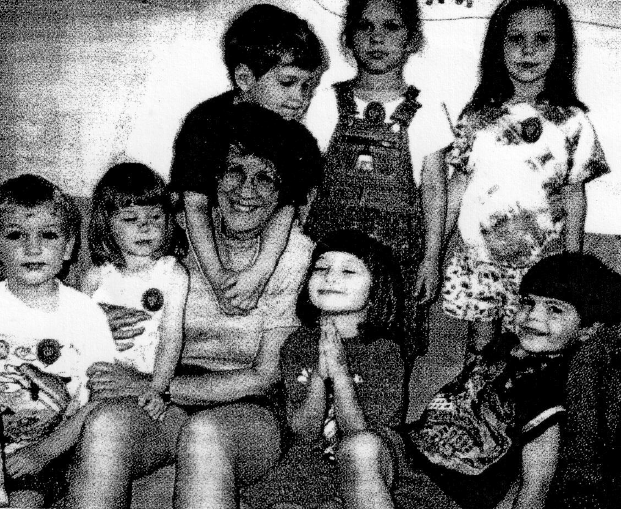

In my memory, Aimee’s three teachers loom over their small charges like friendly giants—Sarah Hyde, Alice Sims and Carol Binstock. I thought of them as Amazons—a trio of formidable women with the no-nonsense clothes or working artists, which is who they were.

“I was seven years,” recalls Alice, who now leads Takoma Park’s Art for the People. “It was one of my favorite jobs I’ve ever had.” I sense immediately that these women would have the strength to restore Aimee’s confidence, and my own. They were patient and empathetic when, constitutionally shy and still reeling from her transplantation, she refused for months to participate in social interactions or even speak much.

Sarah Hyde’s distilled the essence of all the artistic and progressive qualities of Takoma Park. She created the Center in order to be with her young daughter Sophie, and then imbued it with all of her Takoma Park values. There was no rigid philosophy, though Sarah had a Master’s degree in education and extensive experience teaching deaf children. “It was the best of everything rolled together: Waldorf, Montessori …. ” says Marika. At snack time, the kids drank Rice Dream. When Carol went to India on a spiritual retreat, she brought back tiny glittering elephants for each child. With a group of only twelve kids, these indulgences wee possible. “Sarah would get you wonderful art supplies,” recalls Alice.

The teachers read constantly to the children, but they often edited the books. “We talked with Sarah about each book we were going to read, and if it put women or men in a category that didn’t show them living to their full potential, we would change it,” recalls Alice. “She had us change the endings. Instead of marrying the prince at the end, the princess got to do whatever she wanted to do. If the book mentioned a “fat woman” she had us say “large, powerful woman” instead. She had us mutilating those books, scratching them up and changing the wording so that nobody was put down.”

“The thing I appreciated the most was that Sarah’s approach was so individual,” says Dianne Hunt, whose son Gabriel was at the Center with Aimee. “There was a very human underpinning. She had a belief system that allowed her to approach kids individually. A lot of different personalities and stages of socialization could be comfortable there together. I loved that there wasn’t an assumption that kids would always be on their best behavior, because they aren’t. Sarah’s approach was that it was important to be part of a community together and you did the best you could.”

Marika’s firstborn, Cheney, is a unique child, with a long list of gifts and challenges, and many people don’t know what to make of him. Many years later, he was officially placed on the “autistic spectrum.” But at the time Marika enrolled him at Sarah Hyde’s, he was a mystery to most adults.

“We had had Cheney assessed by MCPS and various professional,” she recalls. “Other people had a way of framing Cheney that was more about his problems Sarah Hyde always framed him by his strengths. Other people said, ‘He’s a meddler.’ Sarah said, ‘He really likes to touch stuff. He’s mechanical. Let him take apart a toaster.’” The children would line up at the gate to the Center, and Cheney would begin fiddling with the gate lock. Rather than telling him to stop, Sarah made him the officiate gatekeeper, so that he could fiddle with the lock to his heart’s content.

“Sarah gave us a new way of seeing Cheney that wasn’t so negative,” says Marika. “It had a really positive domino effect on our lives.” For years afterward, it was hard to find a school that was right for Cheney, to find teachers that would see him the way Sarah did. Sarah understood Cheney,” says Marika. “She created a high standard for what kind of understanding we could get about him. If you have a teacher who likes you, who sees you for what you are, it can change your outcome.”

Sarah Hyde was a hard act to follow. Just as Aimee was starting to open up at the end of her first year with her, Sarah told us she was going to close the Center the next year and move on to a job teaching art at the Corcoran. Her own daughter was in middle school, and Sarah wanted to spend more time with her, and on her art. Aimee’s little class at Allegheny scattered to different schools for their final preschool year.

My children went on to grow and thrive at the Takoma Park Cooperative Nursery School. But the Sarah Hyde imprint remains on Aimee, and on each child that passed through Allegheny Learning Center. Just months after she closed the school, Sarah’s brain tumor was found. Then, through years of radiation and surgery, drugs and pain, she would walk with slow determination up and down the Pine Avenue hill to downtown Takoma, passing our street. I would stop her and tell her what Aimee was up to. I would stop her and tell her what Aimee was up to. And when she became confined to her bed, I gave Alice a recent poem Aimee had written, and Alice read it to Sarah. She wanted to hear about what all her many children were creating: their poems, their art, perhaps about the toaster they had taken apart and put back together. Her effect on the earth continues to ripple outward in concentric rings around the pink bungalow.